In order to bring the Homo Mimeticus project to an end and launch the field of mimetic studies, Nidesh Lawtoo (prof. at Leiden University) re-turns to the place where theories of mimesis began. Shot on the Acropolis in Athens, Greece, ep. 1 recalls that philo-sophia, or love of wisdom, is born out of a mimetic agon with a mythic wisdom that found in Athena a primary source of inspiration

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Violence & the Oedipal Unconscious: Book Launch

In this book launch of a diptych on Violence and the Unconscious, Nidesh Lawtoo, Marina Garcia-Granero and William Johnsen present the latest output of the ERC project Homo Mimeticus. Rather than entering the debate on media violence from a quantitative perspective, the book retraces the genealogy of the concept of catharsis that still informs, or misinform the popular imagination. The launch contextualizes the book within mimetic studies and discusses key thinkers of violence and the unconscious, from Aristotle to Nietzsche, Freud to Girard, among others. More information here: https://msupress.org/9781628964851/vi…

Keynote III. Arks at Sea, Arcs of Time (William E. Connolly)

What adjustments in established debates about the character of time, culture/nature relations and mimetic processes are suggested when you treat the evental register of time to be a fundamental feature of time itself? Michel Serres, Joseph Conrad and Nidesh Lawtoo are drawn upon to help explore time as a multiplicity, thinking time to be composed of multiple temporalities moving at different speeds and on different trajectories

Premiere: Jean-Luc Nancy on Philosophy & Mimesis Video

Tune in on Thursday, October 8, at 8pm for the premiere of the latest episode of HOM Videos, Jean-Luc Nancy: Philosophy and Mimesis. Topics discussed include the relation between philosophy and literature, myth, politics and community. Sign up via this link:

HOM Seminar Reloaded: from Poststructuralism to Posthumanism

Join us for the first session of the HOM Seminar on Friday, October 2, 4pm, Room N, Institute of Philosophy, KU Leuven. Presentations by Nidesh Lawtoo on the “mimetic turn”, new HOM-team member Carole Guesse on “posthuman mimesis,” and discussion of an interview with J. Hillis Miller, supplemented by a screening of Jean-Luc Nancy. More details here: https://hiw.kuleuven.be/hua/events/hom-seminar

Please register by sending an email to: niki.hadikoesoemo@kuleuven.be

Allegories of Contagion: Jean-Luc Nancy on (New)Fascism, Democracy, and COVID-19

In a forthcoming interview for HOM to be published in a special issue of CounterText dedicated to examining what we call a mimetic re-turn in the post-literary sphere, Jean-Luc Nancy and Nidesh Lawtoo take a deep look at various mimetic phenomena that characterize the current condition of homo mimeticus, among them the recent surge of (new)fascist tendencies in contemporary democracies and the COVID-19 crisis. Both (new)fascism and viral contagion are paradigmatic mimetic phenomena—but how are they related?

Let’s begin with what Lawtoo calls (new)fascism. For Nancy, the recent surge in this phenomenon owes to a crisis resulting from a condition that belongs to the very definition of democracy. In a democracy, Nancy argues, there is nothing that stands in for its representative, the demos, until the performative moment—paradigmatically in the French Revolution—in which the people names itself as such: “we, the French people declare…” In this sense, Nancy says, democracy is perhaps a kind of “mimesis without a model” as theorized by his collaborator, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe. Fascism’s recurring trick, both in the early twentieth century and today, consists in taking advantage of technological and economic crises to declare itself as “the truth of the people,” thus giving the people a figure, a series of representations that seek to fill a spectral absence at the heart of democracy by presenting themselves as the people itself. While the symbols employed by early twentieth century forms of fascism consisted of imagery and symbolism drawn from ancient Rome, contemporary figures combine more multifarious sources in the absence of the unifying force that classical culture held under Hitler and Mussolini.

Moreover, Nancy continues, political philosophy since Rousseau conceives the community as an organism in which all its parts are integrated into a unity whose end is itself and which subordinates some parts of the body to others according to their function. “If I am the little finger,” Nancy quips, “I cannot do as many things as, for example, the eye can.” Early fascisms have taught us that carrying this organic metaphor to completion is not only impossible, but leads to unimaginable catastrophes. On the other hand, however, the relative disappearance of the nation today also poses problems for state democracies, whose unity consists of mere remainders in immense technological and economic networks that leave subjects feeling lost, abandoned, purposeless. For Nancy, this is an aporetic condition: either one projects oneself completely to the outside—“thus one is necessarily a philosopher or an artist”—but ends up detached from society, or one mourns the loss of the nation while building the kind of resentment that Nietzsche and Scheler described as the consequence of the unbearable loss of connection.

In this respect, Nancy says, the recent COVID-19 pandemic “offers us a magnifying mirror of our planetary contagion.” Indeed, as Nidesh Lawtoo has noted in a recent post for The Contemporary Condition, this crisis is a mimetic phenomenon in more than one way: not only because of the literally viral process of copying that enables it to reproduce itself through other living beings, but because of how it renders subjects vulnerable to affective contagion—from anxiety and panic to solidarity and sympathy.

Nancy’s “magnifying mirror,” also affords him an opportunity to envision the difficulties the crisis portends for our collective futures:

We have the same fears, the same expectations—the end of capitalism and the beginning of ecological cleansing or, on the contrary, threats to freedom—and everything is extremely expected, repetitive, and codified. At the same time, it is a contagion that is developing less perhaps because of the severity of the sanitary risks than because of the important differences between countries, governments, and opinions. All of a sudden, the world seems deprived of direction or support. All of a sudden, states become important again. All of this moves slowly towards a tomorrow which will be complicated and conflictive in various ways, since it will be mixed with ecologic problems that are still awaiting our attention—and all of this will take place in what, as it seems, will be a very problematic economy.

But the interesting question is whether something can produce a new contagion: something new that I will call spiritual, as this is where things must go. I would like to say through the spirit of a world. It was through the plagues and the wars of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that Europe invented humanism and capitalism, classical art, the thoughts of reason and experience as well as literature. Machiavelli described the plague in Florence at the same time as he developed a concept of the modern state. However, he and the others of his time did not have behind them a history that had run out of breath…

The mirror is an old metaphor for mimesis—as old as Plato’s denunciation of the ontologically-degraded status of what is reflected on its surface. A magnifying mirror, however, calls attention to the effect that the mirror itself has upon what is reflected—it exposes the trick that Plato intended to carry out by dubbing the products of mimesis an unsubstantial reflection. The magnifying mirror transforms that supplementary reflection into a tool for detailed analysis, an analysis that, unlike a magnifying glass, is not directed at an object but at the subject itself—it is not a tool for theoria or contemplatio but one forreflectio. As in the overarching trope of the mirror in Renaissance vanitas paintings (contemporaries of the turning points, the krises, that Nancy evokes), the mirror also reveals veritas: the motivations, inclinations of the onlooker and, in case of memento mori paintings, of their mortal—and mimetic—condition.

Allegories, as Walter Benjamin once noted, reveal truth as a historical process of decay. To follow Nancy in approaching the virus as a magnifying mirror is to remember that the true causes of the crisis lie elsewhere: in the unequal conditions caused by global capitalism, in the supplementary role of (new)fascist leaders that presume to give a figure to a people that does not appear as such, in the technological co-optation of attention and information through digital media that allow for (new)fascist leaders to shape global narratives; as this happens, biological contagion continues its spread—disproportionately affecting the most vulnerable racialized populations in North and South America—leaving in its wake a death-toll whose official numbers are but a phantom of the true extent of the crisis.

Daniel Villegas Vélez

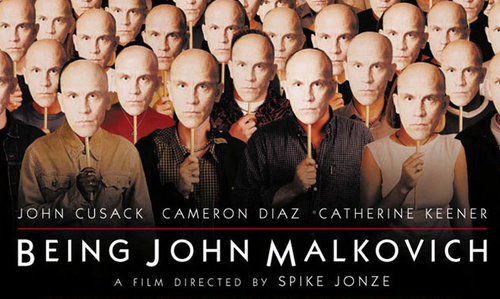

New Article on Spike Jonze’s Hypermimesis

What do contemporary films tell us about the material effects of theatrical, cinematic, and digital simulations? This article considers Spike Jonze’s mimetic aesthetics in Being John Malkovich (written by Charlie Kaufman; 1999) and Her (2013) to diagnose the transition from a society of the spectacle based on embodied forms of mimesis to a network society in which digital simulations have material effects on posthuman bodies and souls, or hypermimesis. Full article available here.

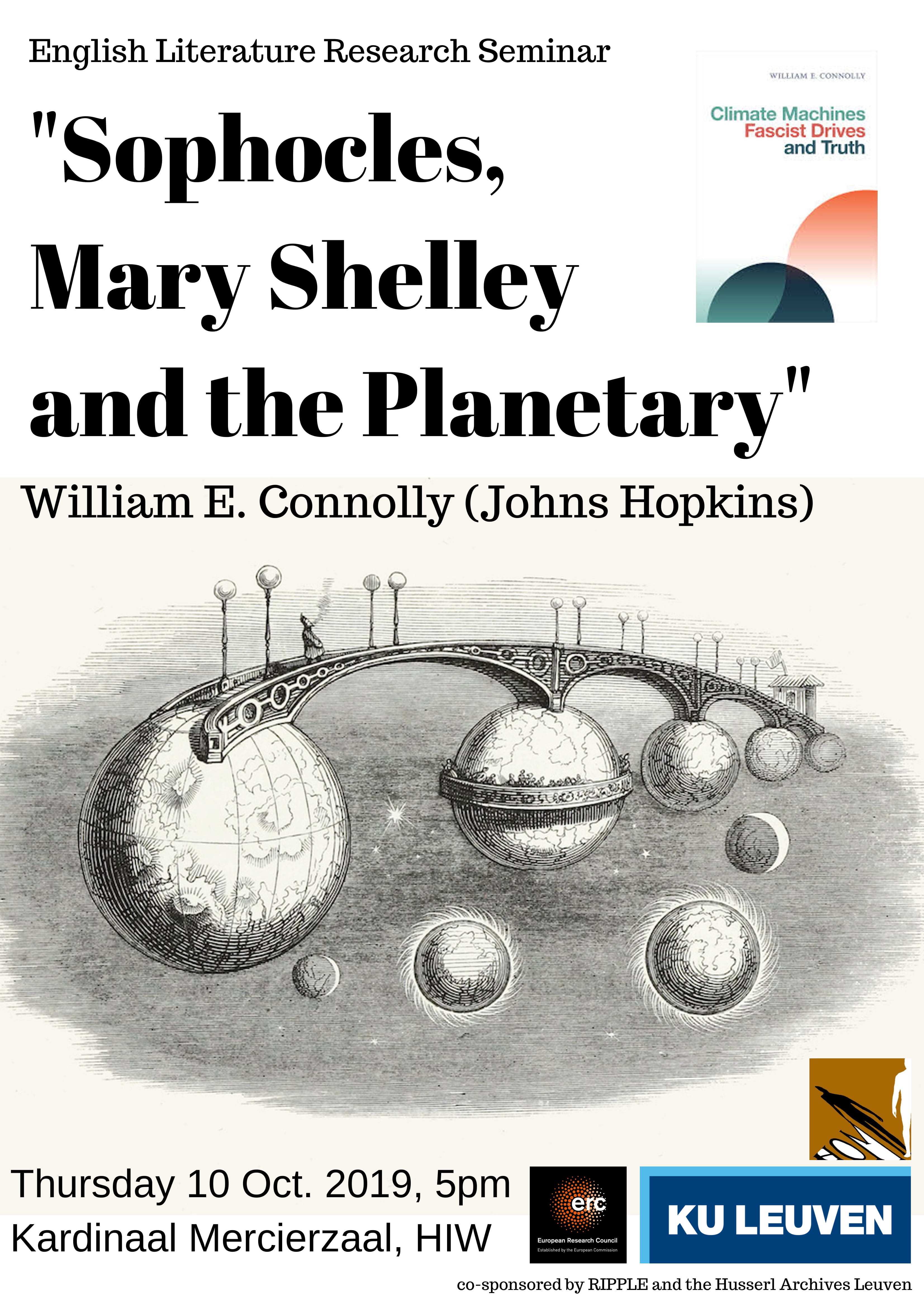

William E. Connolly Lecture: Sophocles, Mary Shelley, and the Planetary (Oct. 10, 2019)

In this lecture co-sponsored by the English Literature Research Seminar, RIPPLE, the Husserl Archives and the HOM project, political theorist William E. Connolly (Johns Hopkins Univesity) focuses on three diverse thinkers – Sophocles, Mary Shelley, and Bernard Williams. Writing in different times and places they advanced overlapping insights that, if widely absorbed in major Eurocentric theories, may have advanced insights sooner into the unruliness of the earth.

Thursday October 10, 5 pm, Kardinaal Mercierzaal, Institute of Philosophy, KU Leuven. Reception to follow. More details here.

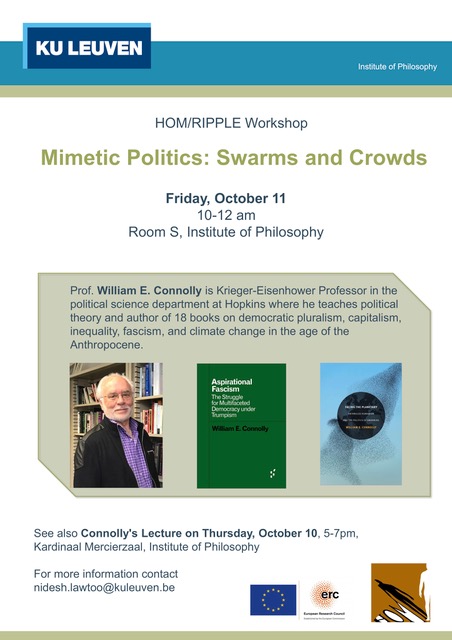

The lecture is followed by a workshop on “Mimetic Politics: Swarms and Crowds” Friday, October 11, 10-12pm. Radzaal, Institute of Philosophy. All welcome. Details and readings here.

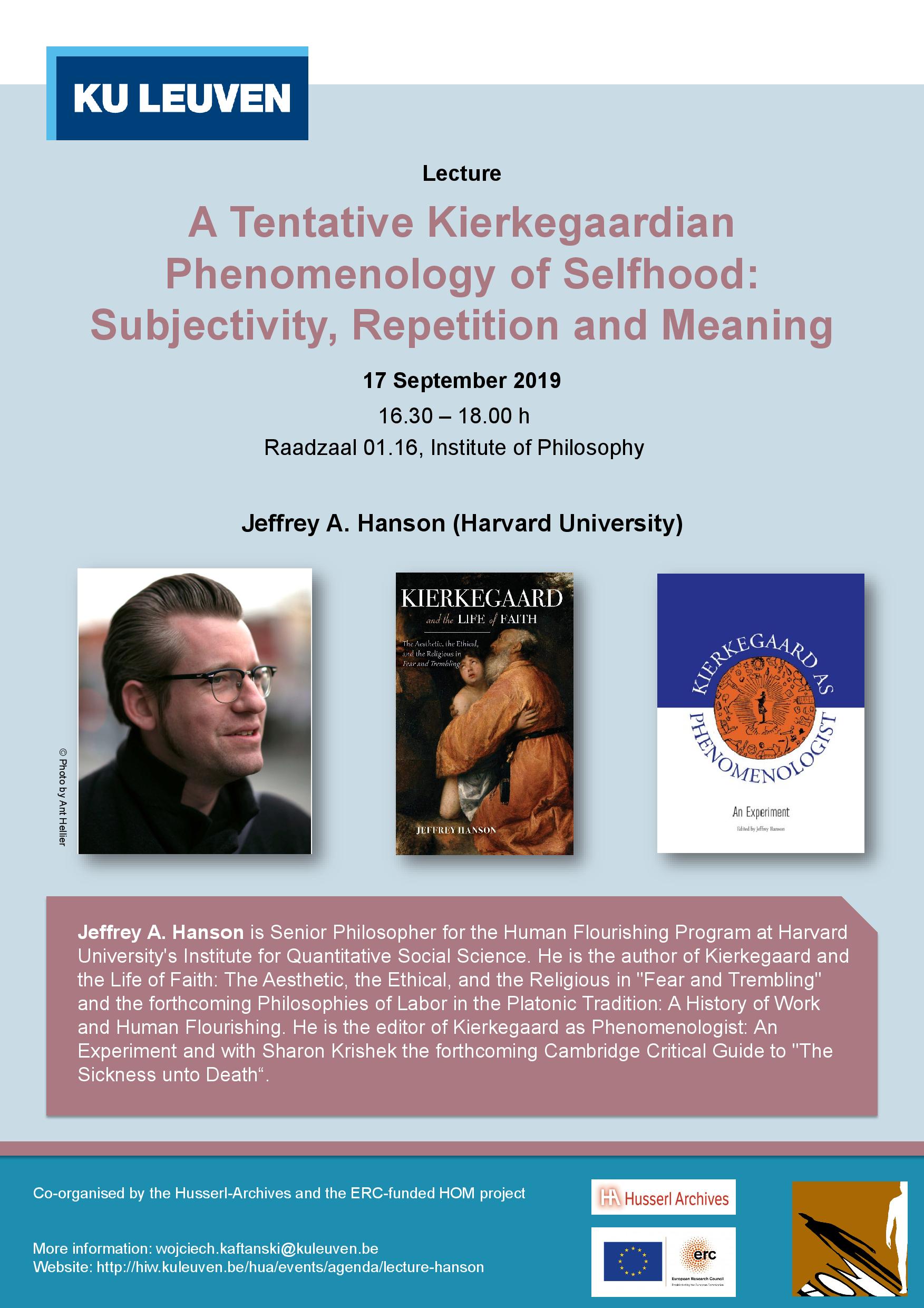

Invited Talk: Jeffrey Hanson (Harvard University), A Tentative Kierkegaardian Phenomenology of Selfhood

In this talk, Prof. Jeffrey Hanson argues that liturgical language used by Vigilius Haufniensis in Kierkegaard’s The Concept of Anxiety is of critical significance to his account of earnestness, which in turn is at the heart of his theory of selfhood. Tuesday, September 17, 4:30-6 pm, Raadzaal, Institute of Philosophy (reception to follow). More details here: